Bias Is a Big Problem. But So Is ‘Noise.’

By Daniel Kahneman, The New York Times

By Daniel Kahneman, The New York Times

The word “bias” commonly appears in conversations about mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions. We use it when there is discrimination, for instance against women or in favor of Ivy League graduates. But the meaning of the word is broader: A bias is any predictable error that inclines your judgment in a particular direction. For instance, we speak of bias when forecasts of sales are consistently optimistic or investment decisions overly cautious.

Society has devoted a lot of attention to the problem of bias — and rightly so. But when it comes to mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions, there is another type of error that attracts far less attention: noise.

To see the difference between bias and noise, consider your bathroom scale. If on average the readings it gives are too high (or too low), the scale is biased. If it shows different readings when you step on it several times in quick succession, the scale is noisy. (Cheap scales are likely to be both biased and noisy.) While bias is the average of errors, noise is their variability.

Too Much of a Good Thing—Overly Positive Online Ratings—Makes for Difficult Decisions

By Evan Nestak, Behavioral Scientist

By Evan Nesterak, Behavioral Scientist

My girlfriend, Klára, considers herself something of a movie buff. For the most part this is a good thing. I have a trusted and reliable source for what to watch when it’s time to kick back.

But there is a downside.

Whenever I suggest something to watch, she’s pretty skeptical. Her first reaction is to check the ratings online and report back that, just as she suspected, the movie can’t be any good because it’s only been rated seven-and-a-half stars. She’ll trust me with big financial decisions, for instance, but a 90-minute movie seems a step too far. For that, she’d rather believe a group of strangers on the internet.

But how reliable are those movie ratings? A series of studies (open-access), recently published in Nature Human Behaviour, suggests those ratings might not be the best way to pick your next movie. A research team, led by Matthew Rocklage, assistant professor of marketing at the University of Massachusetts–Boston, explored how online ratings (e.g., four out of five stars) of movies, restaurants, books, and commercials related to that thing’s success. The team also explored how the language people use in reviews, particularly the level of emotion, related to success. What the researchers found was that emotionality of reviews did a better job than star rankings at predicting which reviewee performed better—more box office sales for movies, more reservations for restaurants.

This is in part because ratings tend to skew heavily positive, so much so that the ratings cease to be useful in differentiating between one movie or another, something Rocklage and his collaborators have dubbed the positivity problem. (It’s curious to think that positivity could be a problem online, when we so often focus on the issues caused by negativity in the digital sphere.)

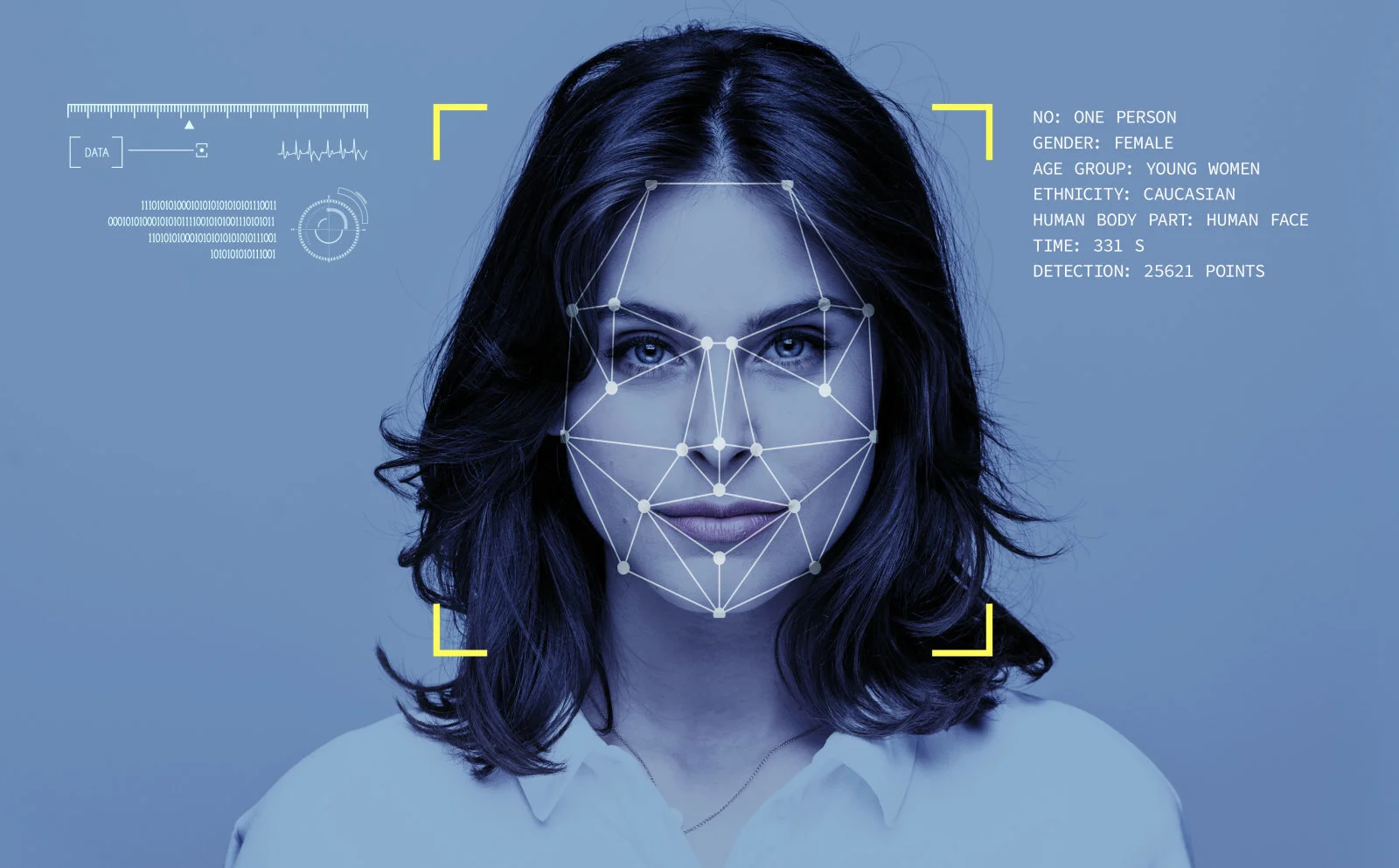

Artificial Intelligence Is Misreading Human Emotion

By Kate Crawford, The Atlantic

By Kate Crawford, The Atlantic

At a remote outpost in the mountainous highlands of Papua New Guinea, a young American psychologist named Paul Ekman arrived with a collection of flash cards and a new theory. It was 1967, and Ekman had heard that the Fore people of Okapa were so isolated from the wider world that they would be his ideal test subjects.

Like Western researchers before him, Ekman had come to Papua New Guinea to extract data from the indigenous community. He was gathering evidence to bolster a controversial hypothesis: that all humans exhibit a small number of universal emotions, or affects, that are innate and the same all over the world. For more than half a century, this claim has remained contentious, disputed among psychologists, anthropologists, and technologists. Nonetheless, it became a seed for a growing market that will be worth an estimated $56 billion by 2024. This is the story of how affect recognition came to be part of the artificial-intelligence industry, and the problems that presents.

When Ekman arrived in the tropics of Okapa, he ran experiments to assess how the Fore recognized emotions. Because the Fore had minimal contact with Westerners and mass media, Ekman had theorized that their recognition and display of core expressions would prove that such expressions were universal. His method was simple. He would show them flash cards of facial expressions and see if they described the emotion as he did. In Ekman’s own words, “All I was doing was showing funny pictures.” But Ekman had no training in Fore history, language, culture, or politics. His attempts to conduct his flash-card experiments using translators floundered; he and his subjects were exhausted by the process, which he described as like pulling teeth. Ekman left Papua New Guinea, frustrated by his first attempt at cross-cultural research on emotional expression. But this would be just the beginning.